CAR-5556 and CAR-5503

Testing for CAR-5551 is in Progress.

Please ignore this article. Created just for Testing Purpose.

Testing article date

COVID-19 Nurse Donates Kidney to Boy in Need.

“It’s definitely part of my calling, helping people,” she said. Pikkarainen, a travelling nurse from Minnesota, was working with COVID-19 patients in New Jersey when she heard about Bodie.

Test article English

What Articles Are – es ?

Articles are words that define a noun as specific or unspecific. Consider the following.

Example :-

After the long day, the coup of tea tasted particularly good.

By using article a, we’ve created a general statement, implying that any cup of tea would taste good after any long day.

New Article – es

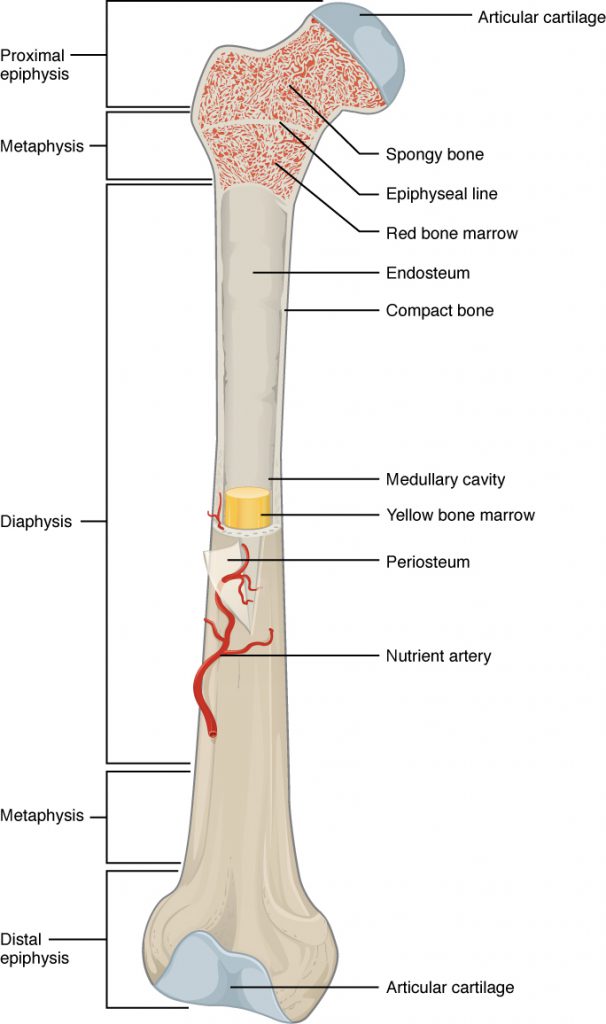

Bone Structure Article-es

The wider section at each end of the bone is called the epiphysis (plural = epiphyses), which is filled with spongy bone. Red marrow fills the spaces in the spongy bone. Each epiphysis meets the diaphysis at the metaphysis, the narrow area that contains the epiphyseal plate (growth plate), a layer of hyaline (transparent) cartilage in a growing bone. When the bone stops growing in early adulthood (approximately 18–21 years), the cartilage is replaced by osseous tissue and the epiphyseal plate becomes an epiphyseal line.

The medullary cavity has a delicate membranous lining called the endosteum (end- = “inside”; oste- = “bone”), where bone growth, repair, and remodeling occur. The outer surface of the bone is covered with a fibrous membrane called the periosteum (peri– = “around” or “surrounding”). The periosteum contains blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic vessels that nourish compact bone. Tendons and ligaments also attach to bones at the periosteum. The periosteum covers the entire outer surface except where the epiphyses meet other bones to form joints (Figure 2). In this region, the epiphyses are covered with articular cartilage, a thin layer of cartilage that reduces friction and acts as a shock absorber.

about eye and vision in spanish

Eye and Vision is an open access, peer-reviewed journal for ophthalmologists and visual science specialists. It welcomes research articles, reviews, methodologies, commentaries, case reports, perspectives and short reports encompassing all aspects of eye and vision. Topics of interest include, but are not limited to, current developments of theoretical, experimental and clinical investigations in ophthalmology, optometry and vision science that focus on novel and high-impact findings on central issues pertaining to biology, pathophysiology and etiology of eye diseases as well as advances in diagnostic techniques, surgical treatment, instrument updates, the latest drug findings, results of clinical trials and research findings.

Eye and Vision is an interdisciplinary journal which covers both ophthalmology and optometry. It will not only focus on the clinical investigations and trials related to ophthalmology, but also give emphasis on the practice and application of optometry. The journal was initiated and is published by Wenzhou Medical University in collaboration with BioMed Central and will provide a common platform for exchange of innovative ideas that helps to bridge the gap in the fields of ophthalmology and optometry.

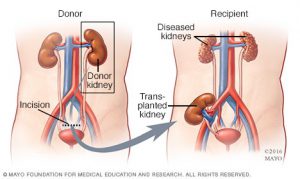

Study of Kidney Transplant

“if you are interested any of the listed studies, please ask your transplant care provider for more information”

This is study 1

Interesting fact 1

My latest Article

WordPress video

Uploaded video

Kidney Post Transplant Care

Introduction

The long term success of a kidney transplant depends on many things. You should:

- Be seen by your transplant team on a regular basis and follow their advice

- Take your anti-rejection medications daily in the proper dose and at the right times, as directed by the transplant team, to keep your body from rejecting your new kidney.

- Follow the recommended schedule for lab tests and clinic visits to make sure that your kidney is working properly.

- Follow a healthy lifestyle including proper diet, exercise, and weight loss if needed

Rejection and Transplant Medicine

What is rejection?

Rejection is the most common and important complication that may occur after receiving a transplant. Since you were not born with your transplanted kidney, your body will think this new tissue is “foreign” and will try to protect you by “attacking” it. Rejection is a normal response from your body after any transplant surgery. You must take anti-rejection medicine exactly as prescribed to prevent rejection.

Are there different types of rejection?

There are two common types of rejection:

- Acute Rejection – Usually occurs anytime during the first year after transplant and can usually be treated successfully.

- Chronic Rejection – Usually occurs slowly over a long period of time. The causes are not well understood and treatment is often not successful.

What are anti-rejection medications?

Anti–rejection (immunosuppressant) medications decrease the body’s natural immune response to a “foreign” substance (your transplanted kidney). They lower (suppress) your immune system and prevent your body from rejecting your new kidney.

Why do I need to take anti-rejection medication?

Kidney rejection is hard to diagnose in its early stages. Rejection is often not reversible once it starts. You should never stop taking your anti-rejection medication no matter how good you feel and even if you think your transplanted kidney is working well. Stopping or missing them may cause a rejection to occur.

How should I take anti-rejection medication?

Here are some tips to help you take your anti-rejection (immunosuppressant) medication as directed:

- Make taking your medicine part of your daily routine

- Use digital alarms and alerts to remember when to take your medication. Be creative because it is easy to forget, especially once you are feeling wellKnow all of your medications by name and dose. Know the reason for taking each medication. Click here for form.

- Ask for and review all written instructions for any change in medication dose or frequency

- Tell your transplant team of problems and concerns about medications during every clinic visit

- If a doctor other than a member or your transplant team gives you a prescription, notify the transplant team before taking. Certain medications can interfere with your anti-rejection medications and keep them from working.

- Continue to take your anti-rejection medication no matter how great you feel, even if you think your transplanted kidney is working well. Stopping them may cause rejection to occur.

Do anti-rejection medications have side-effects?

Anti-rejection (immunosuppressant) medications have a number of possible side-effects which are usually manageable for most patients. Blood levels of anti-rejection medications will be checked regularly to prevent rejection and lessen side-effects. If side-effects do occur, your doctor may change the dose or type of medications.

What are the side-effects of anti-rejection medications?

Some of the most common side-effects of anti-rejection (immunosuppressant) medications include high blood pressure, and weight gain, an increased chance of having infections, and increased risk of some forms of cancer.

What are the types of anti-rejection medications?

There are 3 groups of anti-rejection (immunosuppressant) medications:

- Induction agent – Powerful anti-rejection medication used before the transplant in the operating room, or immediately after the transplant surgery

- Maintenance agents – Anti-rejection medications you will take daily for as long as you have your transplanted kidney

- Rejection agents: Medications which are used for the treatment for rejection episodes

Infection

Why is infection a concern after kidney transplant?

The anti-rejection medicines that help keep your body from rejecting your transplanted kidney also lower your immune system. Because your immune system is lowered, viral and other infections can be a problem.

What is the best way to stay healthy?

Finding and treating infections as early as possible is the best way to keep you and your transplanted kidney healthy. Exposure to diseases such as the flu or pneumonia can make you very sick. Receiving vaccines as determined by your transplant team can help you stay healthy. It is also important to frequently wash your hands or use an antimicrobial gel during cold and flu season.

What problems should I report to my doctor?

You should report any of the following problems to your doctor as soon as possible:

- Sores, wounds, or injuries; especially those that don’t heal

- Urinary tract infection symptoms such as frequent urge to urinate, pain or burning feeling when urinating, cloudy or reddish urine, or bad smelling urine

- Respiratory infection symptoms such as cough, nasal congestion, runny nose, sore or scratchy throat, or fever

How can I avoid getting infections?

To avoid getting infections you should:

- Wash your hands regularly

- Maintain good hygiene habits especially around pets

- Avoid close contact with people who have contagious illnesses

- Avoid close contact with children recently vaccinated with live vaccines (see section on Vaccines). Also, no one in the household should get the nasal influenza vaccine

- Practice safe food handling. For more information on safe food handling go to USDA: Basics for Handling Food Safely

- Inform your doctor well in advance of any travel plans

Vaccines

Can a vaccine be harmful after kidney transplant?

Vaccines help your body protect you from infection. Some vaccines are not good for you when you have a transplant. For example, you should avoid all “live vaccines.” Check with your transplant team before receiving any vaccines or boosters.

What are some general rules for getting vaccines such as Hepatitis B, live vaccines, or a flu shot?

You should:

- Get Hepatitis B vaccine before transplant

- Avoid all live vaccines

- Avoid the nasal influenza vaccine

- Wait at least 3-6 months after transplant before getting a flu shot; then get a yearly booster (injection only)

What if someone I know receives a live vaccine?

You should avoid direct contact with anyone who has received a live vaccine. Examples include:

- Children who have received oral polio vaccine for 3 weeks

- Children who have received measles or mumps vaccines

- Adults who have received attenuated (a-TEN-yoo-ated) varicella vaccine to prevent zoster (attenuated means weaker strength)

- Children or adults who have received the nasal influenza vaccine

What if I travel to another country?

Contact your transplant physician if you plan to travel to another country. You may need to receive certain vaccines to prevent diseases that are common to the area.

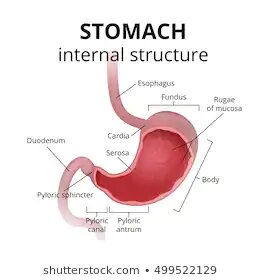

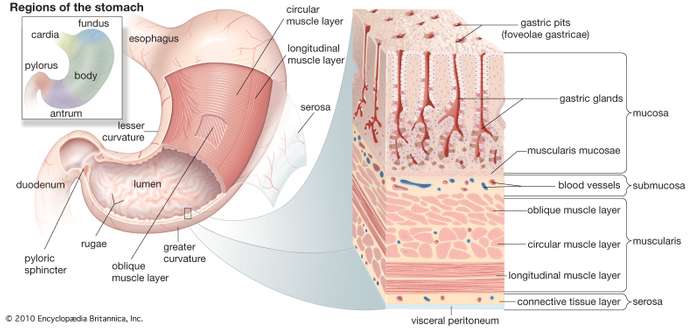

All about the Stomach

Stomach, saclike expansion of the digestive system, between the esophagus and the small intestine; it is located in the anterior portion of the abdominal cavity in most vertebrates. The stomach serves as a temporary receptacle for storage and mechanical distribution of food before it is passed into the intestine. In animals whose stomachs contain digestive glands, some of the chemical processes of digestion also occur in the stomach.

The human stomach is subdivided into four regions: the fundus, an expanded area curving up above the cardiac opening (the opening from the stomach into the esophagus); the body, or intermediate region, the central and largest portion; the antrum, the lowermost, somewhat funnel-shaped portion of the stomach; and the pylorus, a narrowing where the stomach joins the small intestine. Each of the openings, the cardiac and the pyloric, has a sphincter muscle that keeps the neighbouring region closed, except when food is passing through. In this manner, food is enclosed by the stomach until ready for digestion.

Gastrectomy

SURGICAL PROCEDURE

Gastrectomy, surgical removal of all or part of the stomach. This procedure is used to remove both benign and malignant neoplasms (tumours) of the stomach, including adenocarcinoma and lymphoma of the stomach. A variety of less-common benign tumours of the stomach or stomach wall can also be successfully treated with partial gastrectomy. In addition, the operation is sometimes used to treat peptic ulcers because it eliminates the gastric-acid-secreting parietal cells in the stomach lining and halts the production of the acid-stimulating hormone gastrin, thus removing the underlying cellular substances that give rise to an ulcer. Once a common method of treatment for patients with painful ulcers, gastrectomy is now used only as a last resort if the appropriate drugs have failed or if an ulcer is perforated or hemorrhaging.

The most common procedure is antrectomy, which removes the lower half of the stomach (antrum), the chief site of gastrin secretion. The remaining stomach is then reconnected to the first section of the small intestine (duodenum). In a more extensive procedure, subtotal gastrectomy, as much as three-quarters of the stomach is removed, including all of the antrum. The remaining stomach may then be reattached directly to the duodenum or to the jejunum, a more distal part of the intestine beyond the usual site of ulceration.

The long-term survival rates of patients with stomach cancer who undergo gastrectomy vary widely; for example, patients with early stage cancer have high five-year survival rates, typically around 90 percent, whereas patients with late-stage cancers have low five-year survival rates, generally less than 10 percent. Gastrectomy is often accompanied by gastric lymphadenectomy (removal of lymph nodes associated with the stomach), which can improve survival rate in some stomach cancer patients. The incidence of ulcer recurrence after gastrectomy is very low (about 2 percent) when the antrum is completely removed. The most significant drawback to gastrectomy is general malnutrition, caused by decreased appetite and by the stomach’s decreased ability to digest food.

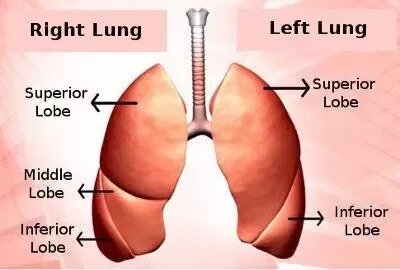

Breathtaking Lungs: Their Function and Anatomy

Overview

The lungs are the center of the respiratory (breathing) system.

Every cell of the body needs oxygen to stay alive and healthy. Your body also needs to get rid of carbon dioxide. This gas is a waste product that is made by the cells during their normal, everyday functions. Your lungs are specially designed to exchange these gases every time you breathe in and out.

Let’s take a closer look at this complex system.

Lung anatomy

This spongy, pinkish organ looks like two upside-down cones in your chest. The right lung is made up of three lobes. The left lung has only two lobes to make room for your heart.

Bronchial tree

The lungs begin at the bottom of your trachea (windpipe). The trachea is a tube that carries the air in and out of your lungs. Each lung has a tube called a bronchus that connects to the trachea. The trachea and bronchi airways form an upside-down “Y” in your chest. This “Y” is often called the bronchial tree.

The bronchi branch off into smaller bronchi and even smaller tubes called bronchioles. Like the branches of a tree, these tiny tubes stretch out into every part of your lungs. Some of them are so tiny that they have the thickness of a hair. You have almost 30,000 bronchioles in each lung.

Each bronchiole tube ends with a cluster of small air sacs called alveoli (individually referred to as alveolus). They look like tiny grape bunches or very tiny balloons. There are about 600 million alveoli in your lungs. The small bubble shapes of the alveoli give your lungs a surprising amount of surface area — equivalent to the size of a tennis court. This means there’s plenty of room for vital oxygen to pass into your body.

The respiratory system

The lungs are the main part of the respiratory system. This system is divided into the upper respiratory tract and the lower respiratory tract.

The upper respiratory tract includes the:

- Mouth and nose. Air enters and leaves the lungs through the mouth and nostrils of the nose.

- Nasal cavity. Air passes from the nose into the nasal cavity, and then the lungs.

- Throat (pharynx). Air from the mouth is sent to the lungs via the throat.

- Voice box (larynx). This part of the throat helps air to pass into the lungs and keeps out food and drink.

The lower respiratory tract is made up of the:

- lungs

- trachea (windpipe)

- bronchi

- bronchioles

- alveoli

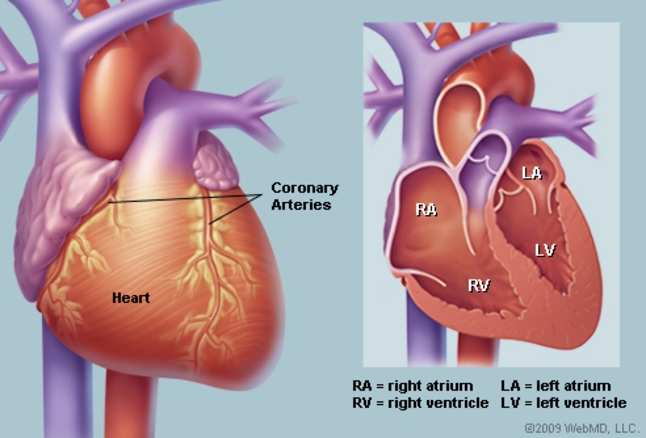

The heart: All you need to know

How the heart works

The heart contracts at different rates depending on many factors. At rest, it might beat around 60 times a minute, but it can increase to 100 beats a minute or more. Exercise, emotions, fever, diseases, and some medications can influence heart rate. For more information on what is “normal,” read this article.

The left and right side of the heart work in unison. The right side of the heart receives deoxygenated blood and sends it to the lungs; the left side of the heart receives blood from the lungs and pumps it to the rest of the body.

The atria and ventricles contract and relax in turn, producing a rhythmical heartbeat:

Right side

- The right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the body through veins called the superior and inferior vena cava (the largest veins in the body).

- The right atrium contracts and blood passes to the right ventricle.

- Once the right ventricle is full, it contracts and pumps the blood through to the lungs via the pulmonary artery, where it picks up oxygen and offloads carbon dioxide.

Left side

- Newly oxygenated blood returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary vein.

- The left atrium contracts, pushing blood into the left ventricle.

- Once the left ventricle is full, it contracts and pushes the blood back out to the body via the aorta.

Each heartbeat can be split into two parts:

Diastole: the atria and ventricles relax and fill with blood.

Systole: the atria contract (atrial systole) and push blood into the ventricles; then, as the atria start to relax, the ventricles contract (ventricular systole) and pump blood out of the heart.

When blood is sent through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, it travels through tiny capillaries on the surface of the lung’s alveoli (air sacs). Oxygen travels into the capillaries, and carbon dioxide travels from the capillaries into the air sacs, where it is breathed out into the atmosphere.

The muscles of the heart need to receive oxygenated blood, too. They are fed by the coronary arteries on the surface of the heart.

Where blood passes near to the surface of the body, such as at the wrist or neck, it is possible to feel your pulse; this is the rush of blood as it is pumped through the body by the heart. If you would like to take your own pulse, this article explains how.